Counting Every Tree

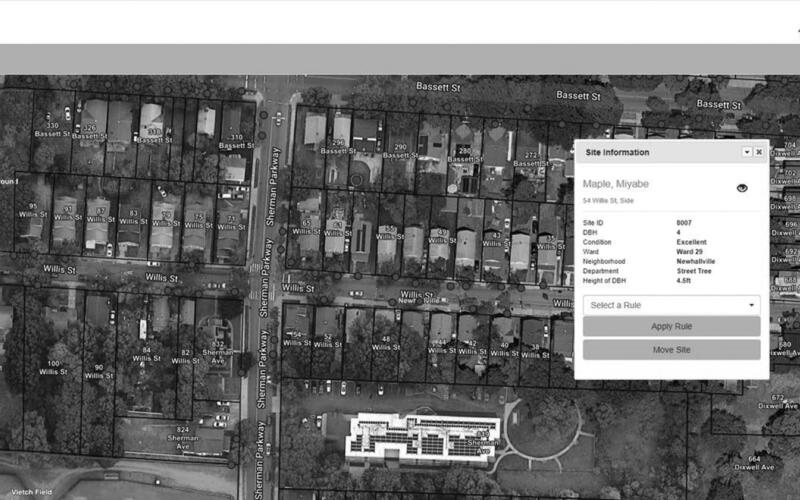

In 2007, the City of New Haven requested URI take over maintaining the citywide street-tree inventory, and it provided the prior comprehensive tree census that had been completed in 2000. URI switched inventory software to TreeKeeper in 2022, enabling the potential for sharing data collection and results with the New Haven Department of Parks and Public Works (DPPW). URI collects field data on tree species, location, diameter, condition, utility-line conflict, inventory date, and date of newly planted trees. The Parks staff updates the TreeKeeper database with any trees they have pruned or removed, and tree stumps they have ground, making space for replacement trees. Having an up-to-date inventory is critical for understanding the species distribution, where the physical gaps are in New Haven’s urban tree canopy, species that are thriving, as well as the trees that have become disamenities. This helps URI plan for greater species diversity and a more resilient urban forest, especially in the face of pests, diseases, and climate change. In 2023, we built upon our 2022 goal by assessing Newhallville and Westville, with a total of 4,614 street trees counted. Of those, we found that 401 trees, or 8.7%, were in conditions of concern—stumps, standing dead, or very poor. We shared this data with our partners at the New Haven DPPW to enable more proactive street-tree management and to reduce the risk of hazardous trees.

Inventory field staff walked through each street of Newhallville and Westville, for a total of 66 miles, and identified, measured, and updated the tree data in TreeKeeper. Oaks, maples, and lindens stood out for their high proportion of each neighborhood’s trees. While trees like tulip poplar, sweetgum, and Amur maackia were not as plentiful, their average condition was often exemplary. Pin oak, Zelkova, Norway maple, London planetree, and lindens were the five most counted trees in Newhallville. In Westville, Norway maple, pin oak, red maple, lindens, and honeylocust were the five most abundant. In both neighborhoods, for example, there was a beautiful Miyabe maple, a common sweetgum, but also an ailing Purpleleaf plum and Callery pear—signs of planting programs gone by, and reminders of the legacy of Urban Renewal in New Haven.

Inventories from URI are helpful for prioritizing and visualizing the needs of New Haven’s trees of concern, and for people to understand the magnitude of the task that is asked of the DPPW. We discussed this with many members of the public who were concerned about potential tree hazards, and connected with people who were admirers of their nearby street tree. One of the most frequent comments that we encountered from people while inventorying trees was about trees of concern. It is the DPPW’s responsibility to remove standing dead and hazardous trees, and several people were grateful to be introduced to the city’s process for that. More often than not, though, people needed a space to grieve the approaching end of their tree’s life, and to share with a listening ear.

Like people, trees have a beginning, middle, and end of life. It is necessary to plan for the end, and to help trees “age gracefully,” both by planting climate-resilient trees and monitoring those already in the ground. Part of monitoring includes staying up to date on current pests and pathogens that are risks to specific species—the emerald ash borer and beech leaf disease, for example. There is a host of experts learning about what is on the horizon for an urban forest in New England who also provide appropriate options of response to these pests and pathogens. By following these steps, we participate in proactive, and not simply reactive, street-tree management.

Across Newhallville and Westville, we recorded many trees planted before URI was established in 1991, and also encountered URI tree adopters throughout both neighborhoods. This speaks to two things—URI’s commitment to planting across New Haven, and also the need for a multi-aged forest structure. One of the big “aha” moments for requesters is that the best time to plant a tree is not always after the large oak comes down—sometimes it is one, five, or even 10 years before. This way, when a tree comes to the end of its life, there is a plan already in place for another tree to serve in its stead. By planting a young sapling next to an aging tree, that sapling has more time to establish itself and to take over more effectively, which also means more moderate temperatures and water-storage benefits for nearby residents.

Additionally, the inventory illustrates that New Haven’s street trees are not spatially distributed evenly across the city. It has also been demonstrated that trees are healthier, and are cared for better, when they are planted where people want them. To continue to plant tree cover equitably, and to replace dying trees, URI needs requesters every year. Having updated online tree databases helps pinpoint areas that would be strategic and viable—places in front of homes and schools, for instance, to guide outreach efforts and to identify new adopters. Even one tree makes a difference in offering not only cooling, habitat, and rainwater-capture benefits, but in beauty and aesthetic value as well. Interestingly, it underscores how most people who request a new free tree from URI learned about the opportunity through word of mouth—a neighbor, a friend, or a community member. Sometimes “just one tree” becomes an occasion for people to gather together—with a common appreciation and perhaps enthusiasm to plant even more!